BLOG- Tomi Ungerer: All in One, by Claire Gilman

In 2015, The Drawing Center in New York held a major exhibition of Tomi Ungerer's work, "Tomi Ungerer: All in One", his first major career retrospective in the United States. The Drawing Center's curator, Claire Gilman, put together the exhibition to redress the lack of platform that Tomi's work has had in the U.S. since his self imposed exile in the early 70s. The show covered a diverse scope of his output, from his childhood drawings depicting the Nazi invasion of Strasbourg, to his editorial and observational works from New York and Canada, political and satirical campaigns, erotic drawings, and finally his illustrations for the 2013 children's book Fog Island. In an essay for the show's accompanying programme, Gilman wrote about the diversity and experimentation of Tomi's output, and how this may have affected his reception from the arts and children's book worlds. Claire Gilman and The Drawing Center have kindly allowed us to reproduce the essay in full here for Tomi's fans and scholars to enjoy.

Tomi Ungerer: All in One, an essay by Claire Gilman.

“No one, I dare say, no one was as original. Tomi influenced everybody.” So spoke legendary children’s book author Maurice Sendak of the iconoclastic Alsatian illustrator Tomi Ungerer, who descended on the New York scene in late 1956. For the next fifteen years, Ungerer’s was a household name in American children’s book publishing and beyond—his drawings appearing in such popular magazines as Harper’s, Holiday, Esquire, Sports Illustrated, and Life.

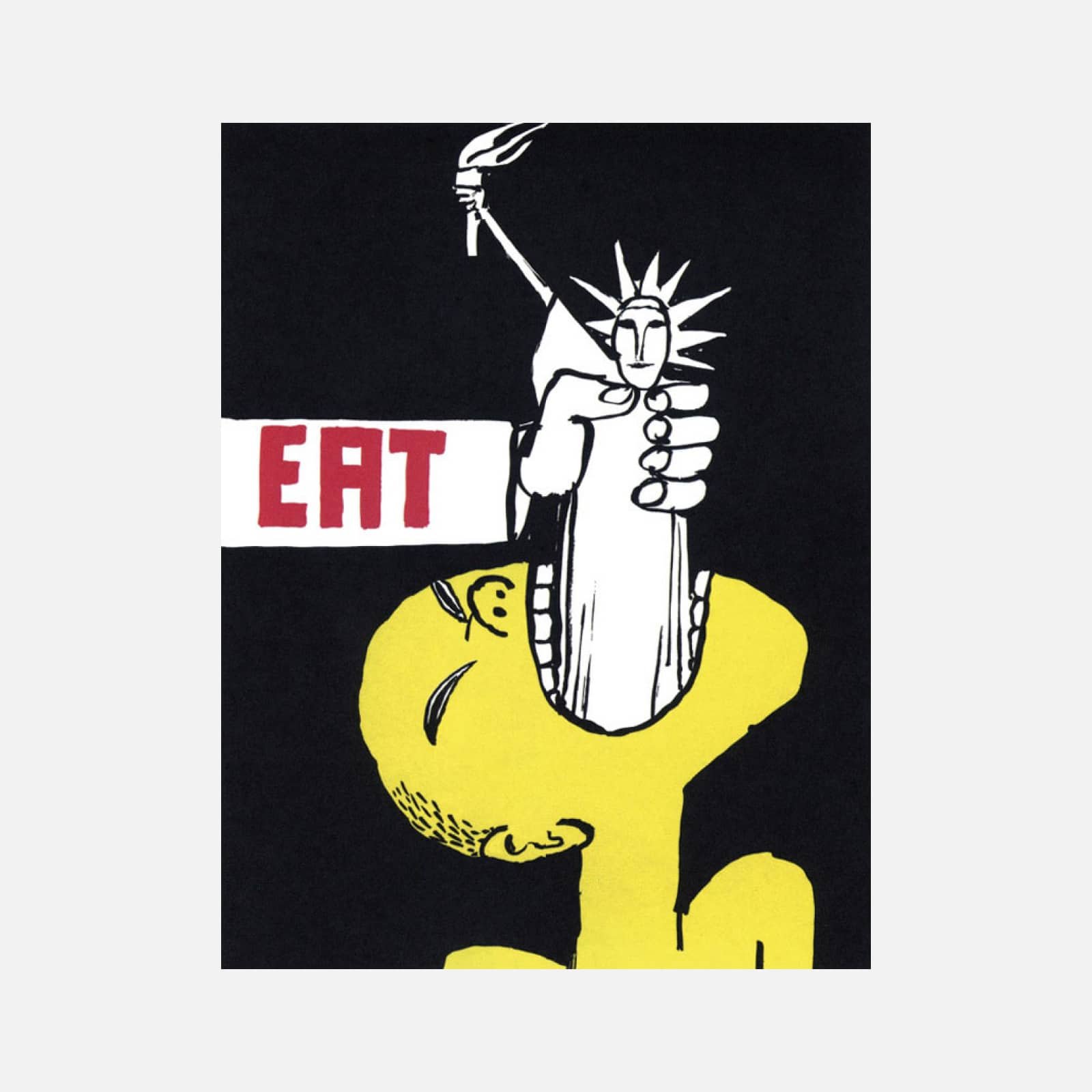

Tomi Ungerer's Poster Art

But despite the industry clout and presence he once held in the United States, Ungerer’s current reputation is geographically circumscribed. Walk into any museum bookstore in France, Italy, and Germany and the artist’s publications line the shelves. Indeed, his renown in Europe extends far outside the literary world to include numerous accolades—not only for his children’s books, but also for his work in advertising, his satirical and political drawings, as well as his longstanding humanitarian efforts. In 2003, he was named Ambassador for Childhood and Education by The Council of Europe; in 2007, he became the first living artist in French history to have a government-funded museum dedicated to his work; and last year he received a lifetime achievement award from the president of France. By contrast, mention his name in the country—let alone the city—where he spent his professionally formative decade and one is apt to draw blank or vaguely reminiscent stares. “Why is this so?” is the question posed by the 2012 documentary Far Out Isn’t Far Enough: The Tomi Ungerer Story; it is also a situation this exhibition aims to redress.

The standard explanation for Ungerer’s relative obscurity in America hinges on the circumstances surrounding his abrupt departure from New York in 1971, a decade and a half after he arrived there from Strasbourg, France. According to an oft-repeated story, the move was precipitated by a juvenile literature convention in which the children’s book establishment took issue with the recent revelation—and the artist’s unapologetic response to it—that the beloved author was also an avid producer of erotica. Fed up with New York’s puritanical ethos, the story goes, Ungerer relocated to a farm in Nova Scotia, with his new wife, Yvonne, where they lived in near seclusion before reentering public life with a permanent move to Ireland in 1976.

While the accuracy of this story is unquestioned, it presents a limited view of the challenges facing an artist who, throughout his career, has engaged not simply in two seemingly contradictory practices, but also in a range of subjects and styles unprecedented in the history of illustration. Ungerer is not a children’s book author who dabbles in erotic fare; rather, he is a multifaceted creative force who has simultaneously participated in major advertising campaigns, limned numerous books of satirical drawings, self-published scathing posters against violence and racial prejudice, and produced exquisite observational sketches and large-scale drawings of rural life. He adopts, moreover, specific and vastly diverse methods—from simple linear pen gestures to fullscale color renderings—to portray images that are variously poignant and tender, dark and ferocious, gently whimsical and bitterly funny. Early on, despite an intense affection for his new city, Ungerer chafed against what he perceived to be an American penchant for strict categorization. As he explains in retrospect, whereas Europe never flinched at his maverick productivity, “somehow you are permitted to be only one thing there [in America]: I was a clown—a children’s-book writer who could also draw.” With hindsight, and within the context of a contemporary art world that prizes crosspollination and the eradication of boundaries, it is precisely this unclassifiability that makes Ungerer’s work so vital and ripe for reassessment. If Europe has been generally more accepting of his eclectic career path, it is undoubtedly in part because Ungerer is himself a product of shifting European identities. Born in Strasbourg in 1931, his creativity was encouraged by a mother who was a talented writer and draftswoman and a father who was an artist, writer, engineer, and astronomical-clock manufacturer. Domestic harmony, however, was short-lived, disrupted by the death of his father when Tomi was three—a loss with which the artist still struggles. Trauma of a more global nature soon followed with the arrival of the Nazis in Strasbourg in 1940 and the annexation of French-controlled Alsace by the Germans.Within the space of three months, the young Tomi was forced to learn German and publically abandon his French ways (thanks to his mother’s ingenuity, the family was allowed to continue speaking French at home). In his revelatory autobiography, Tomi: A Childhood under the Nazis, Ungerer details the daily injustices and barbarism he witnessed, first, under the Germans and, more surprisingly, under the returning French, whose 1945 “liberation” of Alsace he has termed “the greatest disillusion of my life.” As he puts it, “My whole childhood was a schooling in relativity, in figuring out for myself who were the good guys and who were the bad.”

Tomi Ungerer's Childhood Drawings

At the same time, Ungerer developed a fierce pride in his Alsatian heritage, in a people whom he considered strong yet culturally nimble. In his words, “having to adapt ourselves to constant changes has given the Alsatians a great sense of insecurity.” The artist summarizes his departure from his native land for America in 1957 thus: “I packed my rucksack and walked into life, stepping over prejudices and jumping over a lot of conclusions. These excursions into the real world taught me that we are each of us born with a life sentence (which is easier to survive with a smile), that a conscience is more effective when tortured, and that we rid ourselves of prejudices only to replace them with other ones....I learned from relativity, which is food for doubt, and doubt is a virtue with enough living space for every imperfect, sin-ridden, life-loving creature on Earth.”

Instability, doubt, an acceptance—even embrace—of abnormality. If there is a unifying factor in Tomi’s work it is precisely his sustained and deep-felt effort to give voice to the misunderstood and the repressed. This is perhaps most immediately recognizable in his children’s books, the vast majority of which feature outcasts and unlikely heroes. There are the three robbers who turn out to have a soft spot for orphan girls, Crictor the snake and Adelaide the flying kangaroo who convert their handicaps into assets, and the Moon Man who longs to join the throngs on earth only to realize he is happiest alone in space. But Ungerer’s anti-establishment ethos is present in different forms throughout his work: in his assault on American military dominance in the anti-Vietnam War posters; in his inflammatory graphic response to racial injustice, Black Power/White Power, which targets not simply racism against African Americans but extremism on both sides. The same aversion to cultural norms that undergirds beloved texts like The Three Robbers motivates his erotic drawings, grounded as they are in a surprising kind of humanism. Consider the images of brothel workers going about their daily duties in Schutzengel der Hölle (Guardian angels of hell), a project dedicated to dominatrixes in Hamburg whom Tomi came to admire for their service to society’s outcasts. Describing the women’s efforts to fulfill a particularly brutal fantasy, Ungerer observes: “My first line in my book Far Out isn’t Far Enough is ‘What is normal?’ It’s better for a guy like this to find a woman instead of killing a little girl in the woods out of frustration. We have a lot of sick people in this world and we have to acknowledge them. Who does the job?”

Tomi Ungerer: Schutzengel der Hölle

This drive to overturn convention sheds light not only on Ungerer’s choice of subject, but also on his wide-ranging style. Ungerer has described himself as a “selfish” artist who values his own desires at the expense of good taste. I would argue, however, that his approach is profoundly self-less in that he sacrifices himself to the demands of his subjects in a way that many artists would find uncomfortable. (We have already noted that Ungerer’s lack of a single, recognizable style in the manner of Maurice Sendak or Saul Steinberg has hampered his reputation.) What to make of a man who creates caustic political imagery one year and moves to rural Canada where he produces landscapes and studies of farm life worthy of Andrew Wyeth or Winslow Homer the next? How indeed to understand someone who gamely concocts sweetly romantic ink-wash sketches for a German songbook (Das große Liederbuch) and harsh, unforgiving black-pen renderings of death for a volume entitled Rigor Mortis? Ungerer has explained that “what counts is sending a message and, as messages are different, you need different styles.” This is surely true. But beyond the demands of subject matter, it would seem that inhabiting this space of instability constitutes for him a moral and political imperative, bound up as it is in his profoundly humanistic worldview. In Ungerer’s words, “my doubt is open, I tell myself: why not? Everything can be accepted, but everything needs to be questioned” at the same time. Drawing is Ungerer’s way of interacting with the world—as he puts it, “a tool to make my thoughts accessible.”Among the most striking aspects of his method is his tendency to draw and redraw motifs. Rather than use an eraser, Ungerer makes countless sketches. Sifting through them to find the eventually published drawing is a laborious and arguably pointless process. According to the artist, he would rather leave errors than create one perfect composition, a strategy that is evident in his many sketches that include multiple renderings of a subject on a single page, such as an exquisite image that includes repeated profiles of his wife reading to their daughter, Aria. (Ungerer does something similar in several drawings for the erotic book Totempole, imbuing these images of a woman in bondage with an unexpected intimacy.)

In these cases and elsewhere, we see the artist feeling his way through his subject, leaving both himself and his model exposed on the page. Equally deliberate is his choice of pictorial support, typically a kind of tracing paper that, according to Ungerer, allows his ink to run fluidly over the surface. In some drawings, like those for the recent children’s book Fog Island, he lays the background on one side of the paper, letting the color fade out at the edges, and adds foreground elements on the other side, lending the final work an eerie, indefinable cast. Lack of finish, fluidity, uncertainty—once again we are in standard Tomi Ungerer territory.

Tomi Ungerer's original drawings for Fog Island

Ungerer is similarly experimental with line, frequently allowing it to run wild and move in and out of form. Consider the wonderfully excessive curlicues that constitute the telephone wire in Power Line or the deliciously witty cartoons from Der Herzinfarkt (Heart attack) in which lines push and pull, physically stringing their figures along with them. In a particularly lovely sketch from this series, a tiny business-suited man tries to hook an Atalantalike woman with the crook of his cane. As the mammoth female disassembles into calligraphic strokes, her suitor might as well be trying to capture and pin down drawing itself.

It makes perfect sense that Ungerer became a draftsman, and an illustrator at that, rather than a painter like his father; that is, someone called upon to respond to the world around him quickly, repeatedly, and without regard for the dictates of the self-contained aesthetic object. To leave his errors exposed and continue on, such is Ungerer’s way. In this vein, it is important to note that the artist does not place himself above his material, no matter how unsettling the depiction. Whether Ungerer’s target is American commercialism or European provincialism, backwater rednecks or elite society, he freely admits: “I am in all my drawing and books. I don’t say it boastfully, but I’ve performed every one of my fantasies. Maybe it was a way of liberating myself from an uptight and sterile Protestant upbringing. But even while I did all these things, I also rebelled— I repelled myself. And it is this revulsion that comes through so strongly in my work.’’ For example, although Ungerer cannot be accused of directly participating in the atrocities his political posters invoke, one writer observes that their sheer barbarism is implicative, producing in the viewer an equivalent revulsion against the artist’s audacious imagery. “I am a man: nothing that is human is foreign to me,” Ungerer, paraphrasing the Roman playwright Publius Terentius Afer, better known as Terence, has observed—including, one presumes, humanity’s baser impulses. The way forward, his work seems to suggest, is to acknowledge these foibles before seeking a different path.

In Far Out Isn’t Far Enough, Aria Ungerer explains that a huge part of her father’s life has been the quest for an identity. Hence, his peripatetic journey from Strasbourg to New York to Canada and finally Ireland and his work’s obsessive focus on who we are and where we fit in. If the manic flow of his work is any indication, it is a goal that he is no closer to achieving however physically settled he now may be. And yet this non-belonging is itself a place. In Ungerer’s words, “the thing is, if you have no identity you’re free. Your home is no man’s land. You can do anything in no man’s land. This would be a nice fairytale. The child that travels in no man’s land.” This is in essence the story of the recent Fog Island, set mostly in the borderless sea and on a magical island inhabited by a man who controls the fog, which, as described above, employs hazy tones and back-to front color washes to create a sense of distanced unreality. It is an apt concluding work for an Ungerer retrospective (drawings from the book close The Drawing Center’s exhibition), not least because it is a work without conclusion, one in which the final scene returns us to the beginning. The wide open expanses of sea and sky in the Fog Island drawings recall the shadowy hues of The Three Robbers, where a dusky blue serves as both the background and the faces of the robbers who peek through their black cloaks. This is the space of everything and nothing: a space that is perhaps Ungerer’s rightful home.

Originally published in The Drawing Center’s Drawing Papers, Volume 120, January 2015. With thanks to Claire Gilman and The Drawing Center, New York.